This clinical handout contains some of the standard information we convey to clients seeking therapy for PTSD and other trauma reactions. Understanding the rationale for exposure-based therapy strategies can help tolerate the discomfort associated with them. Deliberately re-experiencing trauma memories can be daunting, but can be profoundly beneficial when conducted in a planful way with a skilled therapist.

Some key areas which need to be addressed in psychological therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder are:

- What happened and why (i.e. the nature and context of the traumatic event)

- Anxiety management strategies (PTSD is an anxiety disorder)

- Exposure (Preferably graded and prolonged)

- Social support (Recovery depends in part on the quality and nature of social supports)

A key ingredient of therapy for PTSD is exposure to memories of past traumatic experiences. It is understandable that individuals sometimes wonder why their treatment may require them to re-experience traumatic events from the past which they may have tried for years to put behind them; this is especially so because exposure to past memories can be extremely distressing and people can experience a worsening of their PTSD symptoms for several weeks before their condition improves. Nonetheless, research and experience have demonstrated that such exposure is an important component in the most effective treatments for PTSD. A key stage of individual therapy might be explicitly based on reactivating traumatic experiences in a therapeutic setting, Group therapy discussions may also reactivate memories and feelings associated with trauma. The rationale for using such treatments might become clearer when considering the nature of PTSD.

The Nature of PTSD

PTSD has three main dimensions; these are intrusions or symptoms of re-experiencing trauma, avoidance or numbing, and arousal. Intrusions include symptoms such as nightmares, recurring distressing thoughts and flashbacks; avoidance symptoms include avoiding situations that remind a person of trauma as well as numbed feelings; arousal relates to anxious feelings reflected in startling easily, anger outbursts and panic-like symptoms. Many theories consider intrusive symptoms to reflect an attempt to make a person aware of distressing situations that they haven’t yet dealt with so they have a chance to “work through” their traumatic experience to a more satisfactory resolution. Avoidance and numbing symptoms are designed to reduce the distress or arousal associated with the intrusive symptoms. Although this may lead to short-term relief, it aggravates the problem as it cuts off a person’s opportunity to deal with the past trauma in a different way and thus to put it behind them.

The Storage of Traumatic Memories

In order to understand intrusive symptoms and the need for exposure-based treatments for PTSD it is important to consider how traumatic memories are stored. When a person has a traumatic experience there are several aspects to this experience:

-

Stimulus aspects:

Those aspects of the trauma that relate to sensory experiences and characteristics of the setting in which the trauma occurred; e.g., sights, sounds, smells, physical sensations associated with the trauma.

-

Response aspects:

This relates to the person’s actual reactions at the time of the trauma including emotions such as fear or anger, as well as behavioural reactions such as attempts to escape.

-

Meaning associated with the trauma:

E.g. viewing oneself as unsafe or as incompetent to deal with current challenges.

Each of the above components is stored in a “trauma memory network”. This network might be activated by any experiences which bear a strong resemblance to aspects such as those outlined above; for example, a car backfiring sounds similar to a gunshot and may therefore trigger the traumatic memory network by its association with a trauma-related stimulus. A traumatic memory could likewise be triggered by a response such as feelings of panic or anger related to a particular event. Furthermore, if a person with PTSD ever felt markedly unsafe, this in turn could trigger a trauma memory network because of its link with the meaning of past trauma. What complicates the above situation is that when people are traumatized, their memories can be stored in a disorganized and fragmented way. This means that when a trauma memory is activated, it is not likely to emerge as an integrated or complete re-experience of what actually happened. Indeed parts of the memory can be triggered while other aspects of the memory remain hidden. This means that when a trauma memory network is triggered, a person may experience feelings of panic or even of overwhelming anger without realizing where these feelings come from; for example, only response elements rather than stimulus elements might be triggered. Furthermore, when any one part of a trauma memory network is activated it can trigger any other part of the network without the person necessarily realizing what has happened. Thus a person might experience a recurrence of trauma-related nightmares after finding themselves in a situation many years later when there life was at risk such as after an accident or a life-threatening physical condition such as a heart attack. Owing to the way in which traumatic memories are stored, their effects are real and occur in the present. That is to say the effects are not imaginary and can be genuinely disabling; in order to address such traumatic memories it can be helpful to engage in specific therapy techniques focussing on the sufferers current as opposed to past reactions.

Exposure-based Therapy Treatments

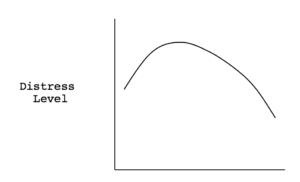

A number of therapy approaches are geared towards activating and restructuring traumatic memories. It is not simply enough to remember past trauma; indeed this in itself could potentially make things worse. A number of therapy techniques are designed to activate traumatic memories in a systematic or structured way and to alter the nature of the memory by incorporating new information, reducing associated fear responses and changing the meaning of the trauma. Some such therapy approaches include systematic desensitization, hypnosis and “Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprogramming” (EMDR). Such techniques can be challenging and distressing and it is common for people to become more distressed during a session or at early stages of treatment before they experience an easing of symptoms and distress. Thus when receiving treatment a person’s anxiety may well follow the curve outlined below. This increase in anxiety before it levels off and subsides is common both across treatment sessions as well as during exposure-based treatment sessions. It is a positive sign during a treatment session if one’s anxiety level reduces to approximately half or less of the peak level by the end of the session. This is an indication of constructive emotional processing of a trauma memory.

Owing to the challenging nature of such treatment strategies it is important that they be conducted by people who are trained in principles of psychotherapy as well as in the specific techniques used. It is important to note that the various exposure-based treatments build in various safeguards to help people manage with the intense distress that may be elicited; these include anxiety management strategies. However, if a person with PTSD does not feel ready to use exposure-based techniques then other approaches should be considered. Where exposure techniques are used, the key to recovery is for a person to find they can face the traumatic memories without being overwhelmed and that they have come to view the traumatic situation in a new way. The intrusive PTSD symptoms then reduce in intensity and there is no longer such a need to use disabling avoidance strategies. The person might then learn that reminders or situations that used to trigger PTSD symptoms are no longer associated with danger.

Chris Mackey is a clinical and counselling psychologist with over 40 years’ psychotherapy experience. He has regularly presented at national and international scientific conferences, including on psychological therapy for trauma reactions.

See our practice’s podcast episode on exposure therapy. Also see our Psych Spiels podcast page for over 100 podcast episodes on various mental health topics with associated links.

For more mental health blogs, therapy articles, videos, etc, see the Resources page of the Chris Mackey and Associates’ website